Realizing Indonesia’s Renewable Energy : An Ambitious Goal or a Mere Dream?

Author: Hapsari Nilakandi • Publish Date: 18/1/2026

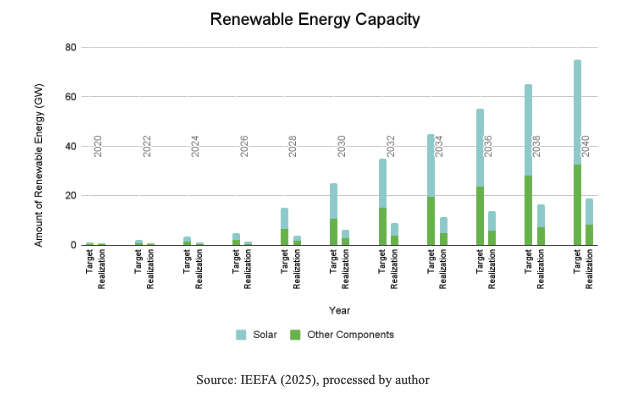

With its abundant rich natural resources, Indonesia holds enormous potential to become a leading nation in renewable energy, driving the country’s long-term sustainability. This ambition is reflected in the government’s renewable energy targets outlined in Rencana Umum Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik (RUPTL), where Indonesia aims to install 75 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy capacity by 2040, primarily driven by solar power additions (taking up over 50%).

A Look into Indonesia’s Renewable Energy Landscape

However, the plan sparked skepticism among experts, who consider it overly ambitious. To meet its 75 GW renewable energy goal by 2040, Indonesia would need to install around 5 GW every year for the next 15 years, an amount roughly equivalent to supplying electricity for about 3–5 million homes for a full day. Yet over the past decade, the country has managed to add only 717 megawatts (MW) of solar capacity, enough to power just around 600,000 homes, resulting in under 20% of what Indonesia should be achieving annually (IEEFA, 2025).

The Unavoidable Challenges that Indonesia Must Face Head-On

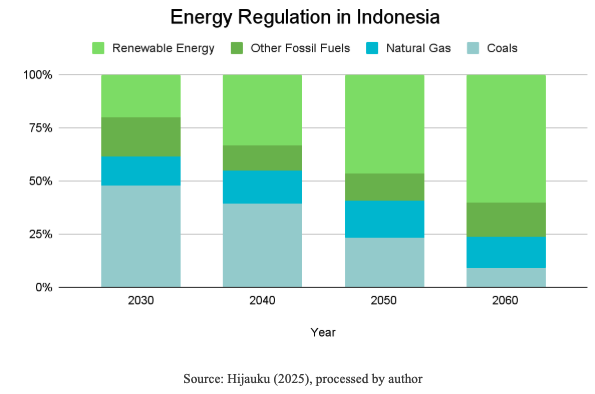

The Indonesian government officially enacted Government Regulation (PP) Number 40 of 2025 on the National Energy Policy (KEN) on September 15, 2025, which serves as the main guideline for Indonesia’s energy development. However, despite being a newly revised framework, the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law (ICEL) argues that the regulation does not advance Indonesia’s renewable energy transition. Instead, it risks pulling the country further backward. According to ICEL, the new KEN lowers Indonesia’s renewable energy ambition and reinforces coal dependence for decades to come. The renewable energy target set in the policy remains far below Indonesia’s technical potential, which exceeds 3,000 GW—reflecting a weak commitment to accelerating the energy transition. As a result, these policies create various obstacles which directly affect businesses because it makes renewable energy harder to access, less affordable, and much less dependable as an investment.

One of the provisions in the new KEN allows a large share of coal to remain in the national energy mix, contradicting Indonesia’s stated ambition to accelerate renewable energy development. This regulation prolongs the lifespan of coal power plants, increases the risk of carbon lock-in, and threatens the achievement of the 2035 emission-peak target and the 2060 net-zero goal. The dominance of coal slows down emission reductions in the energy sector, reduces opportunities for clean-energy investment, and weakens efforts to build national energy sovereignty. In addition to coal, natural gas is also positioned as a long-term energy pillar, with final gas consumption projected to reach 56.6-71.1 million Ton of Oil Equivalent (TOE) by 2060—an amount substantial enough to fuel over 150 million cars for a full year. This dependence risks locking in gas infrastructure, hindering the penetration of renewable energy, triggering stranded assets, and weakening Indonesia’s signal of commitment to fully transition to clean energy.

Indonesia has been providing fossil fuel subsidies since the late 1970s, mainly for poor and vulnerable communities connected to the PLN grid, while many renewable projects operate off-grid, face major integration and infrastructure challenges (Zainal Arifin, 2025). Although these subsidies are officially energy-neutral, in practice, they favor fossil fuel use within the PLN system, making it harder for renewables to compete on equal terms. Massive coal-fired power plant programs, such as the 10,000 MW Fast Track Program and the 35,000 MW National Electricity Program, have also left limited room for renewable energy expansion.

Syaharani, Head of the Climate Justice and Decarbonization Division at the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law (ICEL), stated, “On one hand, Indonesia claims to be committed to decarbonization and achieving net-zero targets, but on the other hand, the government continues to normalize coal use for decades ahead. This means that large investments in gas infrastructure pose the risk of becoming stranded assets.”

Beyond energy policy, financial and investment constraints remain a critical barrier. According to the OECD, financial institutions in Indonesia remain relatively reluctant to provide financing or guarantees to renewable energy companies, largely because clean energy projects are perceived as carrying higher levels of risk. This perception is reinforced by several factors, including limited technical understanding of clean energy projects, insufficient and unverifiable information, and the lack of financial instruments tailored to the sector’s specific needs.

Other than that, Indonesia’s regulatory and institutional barriers continue to hinder business adoption of renewable energy. Insufficient incentives, complex bureaucratic processes, investment uncertainties, and underdeveloped market mechanisms have also made Indonesia way less attractive to renewable energy investors compared to other countries (STIE STEKOM, 2025).

Breaking Down How Policy Stringency and Financial Regulation in a Country Affects Energy Transition

One example of how Indonesia’s policy and financial regulations hinder the shift to renewable energy can be seen in the persistent difficulties surrounding bank financing for sustainable-energy projects. Despite the global push toward green development, data from Transisi Energi Berkeadilan shows that Indonesia’s green investment has remained largely stagnant—averaging only about US$1.5 billion per year (around IDR 23.25 trillion) from 2019 to 2024. In contrast, several neighboring countries record annual green-investment levels well above US$10 billion, making Indonesia’s figure noticeably low.

The core obstacles are rooted not only in project bankability but also in broader structural issues. Indonesia’s renewable-energy sector still operates within a policy environment that lacks strong, consistent enforcement—making long-term investment appear risky for lenders. At the same time, the country’s relatively low financial inclusion rate limits access to affordable financing instruments, especially for small and medium-scale developers that rely heavily on bank loans. Combined with high capital costs and a banking sector that remains more comfortable funding coal-based projects, these factors significantly weaken the financial case for renewables compared to other countries.

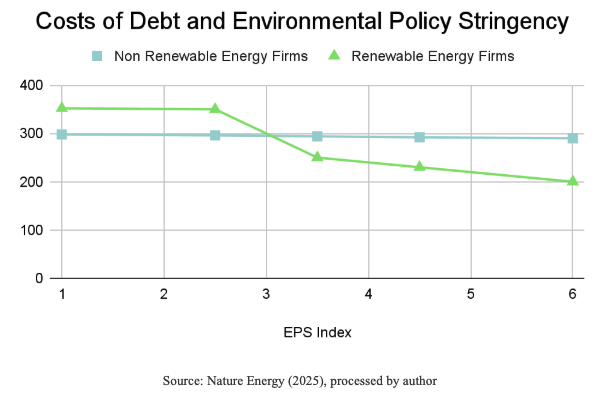

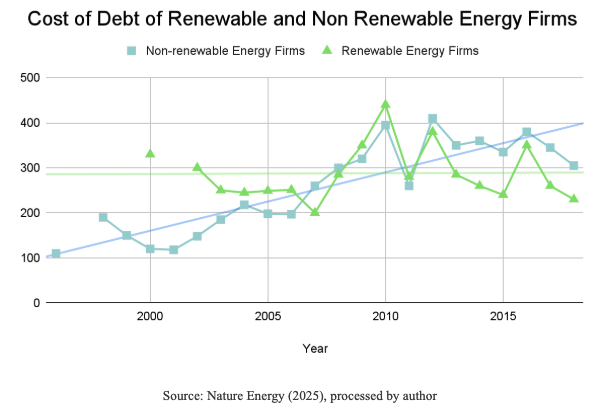

This is a missed opportunity, especially considering that research shows countries with stricter environmental policies tend to offer lower borrowing costs for businesses adopting renewable energy. According to Nature Energy, renewable energy companies in countries with low Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) Index scores have more difficulties to access affordable financing, while countries with higher EPS Index scores allow renewable energy businesses to borrow at lower costs than their non-renewable counterparts, creating a financial environment that actively supports clean energy growth.

Unfortunately, as of 2020, Indonesia’s EPS index remains at 1.65, and there are still no government initiatives that provide profit guarantees or structured financial support for companies seeking to invest in renewable energy (IISPPR, 2024). Electricity tariffs remain unstable, the bureaucracy offers little certainty of consistent returns, and existing green financing programs are still far from being widely accessible.

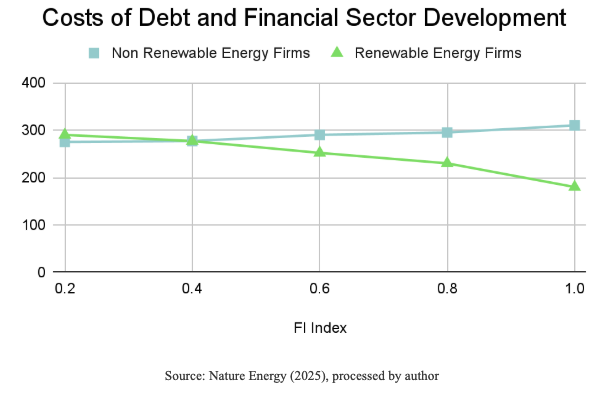

Another dataset also shows that countries with higher Financial Inclusion (FI) Index tend to have lower borrowing costs for renewable-energy firms compared to non-renewable ones. Indonesia, with an FI index of around 0.57—meaning only about 57% of its population has access to formal financial services—sits at a medium level. However, uneven financial literacy and limited access to financial institutions continue to pose challenges. As a result, Indonesia has yet to see the financial advantages that typically support renewable energy companies in more financially inclusive countries.

As a result, businesses, which fundamentally operate to generate profit, are understandably reluctant to transition toward renewable sources that require high cost, especially for the upfront investment, when fossil fuels remain economically superior.

This dynamic shows how financial factors heavily shape the speed of Indonesia’s renewable energy transition. As long as financing remains expensive and risky, renewable projects will struggle to compete with cheaper fossil fuels.

How Implementation Differs Between Indonesia and Global Examples

To better understand how effectively Indonesia is actually performing compared to various cases abroad and the global landscape, a case study of a multinational company in Indonesia, Coca-Cola Amatil, serves as an illustrative example. Coca Cola Amatil struggled to shift toward renewable energy when installing rooftop solar panels at its West Cikarang plant. The company faced high upfront investment costs and a complicated licensing process, with the operational permit alone taking up to six months to obtain. Cases like this are not unique, as many manufacturing companies in Indonesia are struggling to move toward renewable energy due to the complicated and unclear regulations, slow licensing procedures, and high upfront costs. Instead of supporting the transition, the current system often introduces delays and uncertainty at every step.

In contrast, companies in developed countries—particularly in the United States—operate in an environment that significantly simplifies the transition. Intel, for example, has become the largest voluntary corporate purchaser of green power, sourcing 100% of its U.S. electricity needs from wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass. Apple has achieved similar success, running all its facilities in the U.S., China, and 21 other countries entirely on renewable energy. These companies benefit from clear regulations, accessible renewable energy markets, reliable Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), and financial instruments such as Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) that allow them to secure stable, affordable clean energy without excessive bureaucracy.

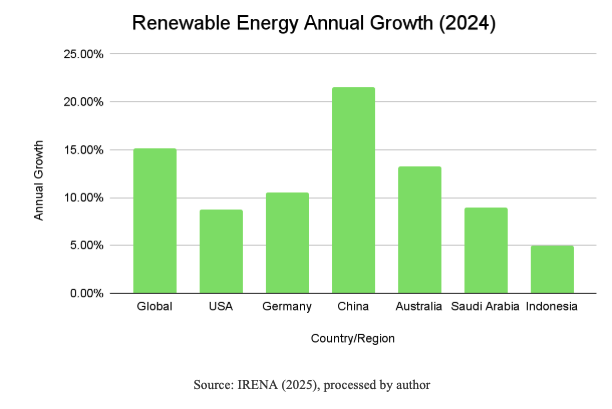

This difference is also reflected in global renewable energy growth trends. In 2024, renewable energy capacity worldwide expanded by 15.1%, with many countries maintaining annual growth rates between 8% and 12%. Meanwhile, Indonesia remains at around 5%, indicating how slowly the country is moving in optimizing its vast renewable energy potential. Together, these comparisons show that while companies abroad can transition smoothly due to supportive policies and well-structured financial systems, businesses in Indonesia continue to face structural challenges that hinder meaningful progress.

Indonesia Isn’t Lacking Potential—We’re Lacking Real Actions

Amid these challenges, the focus should shift toward finding practical ways for businesses to adopt renewable energy without compromising profitability or regulatory compliance. The question now is: what opportunities can companies in Indonesia leverage to make that shift possible?

According to Nature Energy, businesses that use renewable energy actually tend to face lower costs than those relying on non-renewable sources. Before 2007, financing costs for firms developing renewable energy technologies were about 26% higher compared to firms in non-renewable sectors. However, between 2007 and 2018, renewable energy firms ended up paying 19%–27% less for their loans.

This difference occurs due to some factors, but mostly, environmental policy stringency and financial sector development played a key role: the more rigid and consistent a country’s environmental policy and the more competent and effective the financial institutions in a country, the lower the costs of debt of renewable energy firms. These opportunities show what Indonesia could achieve with the right policy consistency, clear incentives, and long-term planning.

In light of these opportunities, the Indonesian government needs to adopt more rigorous environmental policies, not only because stricter rules can help lower the cost of debt for renewable energy companies compared to non-renewable ones, but also because such policies can deliver substantial long-term benefits for the country as a whole: encourage sustainable businesses that are more resilient to energy-market volatility, strengthen economic competitiveness, reduce pollution-related health impacts, and improve overall public welfare.

Beyond stricter environmental policies, strong financial support is also crucial to ease the loan burden faced by renewable energy companies. Incentives, tax reductions, green financing schemes, and targeted subsidies can significantly lower upfront capital costs by addressing the specific financial pain points industries are currently struggling with.

For example, incentives can take the form of guaranteed feed-in tariffs, accelerated depreciation for clean-energy equipment, or direct installation subsidies, similar to approaches that are already proven effective in countries like China. Indonesia has begun adopting similar measures through rooftop-solar incentives and the updated JETP framework, though the implementation remains uneven. Tax reductions can also be made more targeted, following models like Japan’s Green Investment Tax Incentives that reward measurable efficiency gains. On the financing side, Europe’s blended-finance model that combines low-interest green loans, sustainability-linked credit lines, and long-term PPAs has successfully mobilized private capital. Indonesia has early foundations such as the Green Taxonomy and the SDG Indonesia One platform, but expanding access, particularly for SMEs and industrial clusters, will be critical for accelerating adoption.

Aside from the efforts needed from the government, businesses also have to take concrete steps to ensure that the shift to renewable energy is both smooth and profitable. This is especially important, considering many past attempts at adopting green solutions have stalled due to the lack of a clear roadmap, adequate financing, or technologies that were ready for long-term use.

First thing first, businesses should implement a gradual, well-planned approach. Starting with diversifying energy sources, such as solar, wind, and biomass, to ensure a stable supply and mitigates financial risks during the transition phase. Companies such as Google, Tesla, and IKEA have demonstrated that long-term savings and efficiency gains can offset initial expenditures (Emergent Africa, 2023). Approaches like structured energy audits, phased installation of solar rooftops, power-purchase agreements (PPAs), or integrating low-carbon technologies into existing production lines can offer measurable progress instead of one-off pilot attempts.

What Do We Have to Do Now?

Today, as global industries rapidly shift toward cleaner energy systems, the ability of businesses to adapt is becoming a defining factor of competitiveness, and a strategic step that determines whether a company can survive and grow in the long term.

Clean energy doesn’t just reduce emissions—it helps companies stabilize long-term operating costs, protect themselves from volatile fossil-fuel prices, and meet the sustainability expectations of regulators, investors, and global buyers. Businesses that manage to secure affordable renewable electricity or improve efficiency often experience immediate operational savings, smoother regulatory compliance, and better access to international markets that now demand cleaner supply chains. In turn, building a sustainable brand identity strengthens consumer trust and investor confidence, turning environmental responsibility into a clear competitive advantage.

As Indonesia pushes to reach its renewable-energy targets, businesses hold an increasingly important role in redesigning how they consume and produce energy. By adopting practical, trackable steps toward cleaner technologies today, companies can protect their bottom line while contributing to a more resilient, low-carbon national economy. This time, the transition cannot be symbolic; it has to be actionable.

References

Africa, Emergent. “Case studies demonstrating profitability through sustainable operations.” 2023, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/case-studies-demonstrating-profitability-through-sustainable

Arifin, Zainal. “OPINI: Energi Terbarukan Berjalan Lambat.” 2025, https://hijau.bisnis.com/read/20250702/652/1889745/opini-energi-terbarukan-berjalan-lambat

Finka, Dian. “IESR: Biaya Mahal, Pendanaan Jadi Penghambat Transisi Energi.” https://www.kabarbursa.com/ekonomi-hijau/iesr-biaya-mahal-pendanaan-jadi-penghambat-transisi-energi. Accessed 2025.

“Five Major Businesses Powered by Renewable Energy.” The Climate Reality Project, 25 November 2016, https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/5-major-businesses-powered-renewable-energy. Accessed 5 November 2025.

Hauber, Grant. “Realizing Indonesia's ambitious renewable energy goals calls for a new approach.” 2025, https://ieefa.org/resources/realizing-indonesias-ambitious-renewable-energy-goals-calls-new-approach.

IESR. Indonesia Energy Transition Outlook 2024, 2024, https://iesr.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Indonesia-Energy-Transition-Outlook-2024-1.pdf.

Kempa, Karol, et al. The cost of debt of renewable and non-renewable energy firms.

Koons, Eric. “Environmental Issues In Indonesia: A Growing Concern.” Climate Impacts Tracker Asia, 7 February 2024, https://www.climateimpactstracker.com/environmental-issues-in-indonesia-a-growing-concern/. Accessed 5 November 2025.

“Mendorong Dekarbonisasi Sektor Industri di Indonesia melalui Energi Terbarukan dan Efisiensi Energi.” IRID | Indonesia Research Institute for Decarbonization, 5 February 2025, https://irid.or.id/mendorong-dekarbonisasi-sektor-industri-di-indonesia-melalui-energi-terbarukan-dan-efisiensi-energi/. Accessed 5 November 2025.

“Peluang dan Tantangan Bisnis Energi Terbarukan bagi Generasi Muda Indonesia.” stie stekom, 11 August 2025, https://stiestekom.ac.id/berita/peluang-dan-tantangan-bisnis-energi-terbarukan-bagi-generasi-muda-indonesia/2025-08-11. Accessed 5 November 2025.

PWC. “Mining in Indonesia Investment, Taxation and Regulatory Guide.” 2025, https://www.pwc.com/id/en/energy-utilities-mining/assets/mining-guide-2025.pdf.

Simanjuntak, Uliyasi. “Indonesia Has 333 GW of Financially Viable Renewable Energy Projects.” IESR, 27 February 2025, https://iesr.or.id/en/indonesia-has-333-gw-of-financially-viable-renewable-energy-projects/. Accessed 5 November 2025.

TEMPO. “Baru Disahkan, PP Kebijakan Energi Nasional Dinilai Persulit Transisi ke Energi Bersih.” 2025, https://apbi-icma.org/id/media-article/baru-disahkan-pp-kebijakan-energi-nasional-dinilai-persulit-transisi-ke-energi-bersih.

Source Addition.

Comments

No comments for this post