Towards a Sustainable Future: Unbottling the Challenges Behind Indonesia’s Green Finance Stagnation

Author: Najwah Ariella Puteri • Publish Date: 24/11/2025

In recent years, the growing emphasis on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the green economy has spurred a surge of green projects and businesses across Indonesia. Initiatives such as the Green Hydrogen Plant (GHP) and various renewable energy (Energi Baru Terbarukan/EBT) developments have become central to Indonesia’s sustainability agenda. These efforts align with the country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 2030) under the 2015 Paris Agreement, which aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 31.89%.

Introduction: Indonesia’s Green Finance Ecosystem Is Growing but Stagnation Remains

In recent years, the growing emphasis on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the green economy has spurred a surge of green projects and businesses across Indonesia. Initiatives such as the Green Hydrogen Plant (GHP) and various renewable energy (Energi Baru Terbarukan/EBT) developments have become central to Indonesia’s sustainability agenda. These efforts align with the country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 2030) under the 2015 Paris Agreement, which aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 31.89%.

To support this transition, the government through Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK) introduced the Green Taxonomy 1.0 in 2022. This framework classifies environmentally sustainable economic activities based on their alignment with specific environmental objectives and targets (UN ESCAP, n.d.). The taxonomy serves as a guide for directing capital toward sustainable projects that contribute to environmental goals by providing a common reference for companies, investors, and policymakers. Furthermore, it enhances transparency and accountability in green investments, thereby reducing investor uncertainty and minimizing the risks of greenwashing.

As sustainability challenges continue to evolve, such as climate change and industry downstreaming, the government has committed to regularly updating the taxonomy to accelerate progress toward the SDGs. In 2024, the Financial Services Authority (OJK) released the Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (TKBI) 1, followed by TKBI 2 in 2025, that aims to enhance capital allocation and promote sustainable financing for green activities. Therefore, the implementation of the green taxonomy has direct implications for the financial sector, particularly in guiding capital allocation and risk assessment. By defining which economic activities qualify as sustainable, it provides financial institutions with a clear framework for evaluating, developing, and integrating ESG principles into lending and portfolio strategies. Consequently, it plays a critical role in aligning the flow of finance with national sustainability objectives, fostering a more resilient and low-carbon financial system.

However, even with a clear guidance on green investments, Indonesia’s green financing remains low. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (2024), while total investment demand for green activities is estimated at USD 285 billion, the available financing only reaches USD 146 billion, covering merely 48.77% of the total need. This finding contrasts with data from the Asian Development Bank (ADB, 2022), which indicates that around 81% of investors express interest in green investments. This disparity raises concerns about the feasibility and practical implementation of Indonesia’s sustainable development agenda.

Therefore, this article will explore three underlying reasons why green financing in Indonesia remains stagnant, despite the increasing global and national momentum toward sustainability.

Three Underlying Causes of Green Financing Stagnation in Indonesia

1. Regulatory Uncertainty

One of the most significant barriers to advancing green financing in Indonesia lies in the persistent regulatory uncertainty surrounding sustainable investment frameworks. Long-term and large-scale green projects such as renewable energy projects depend heavily on policy stability and predictable regulatory environments to ensure investment security. However, Indonesia’s policy framework on sustainability continues to evolve every year, creating ambiguity for investors and financial institutions.

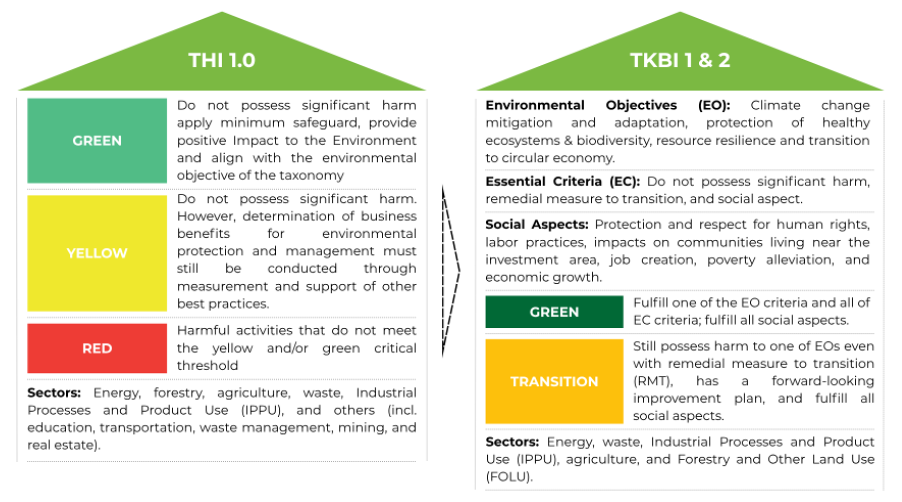

Figure 1. Comparison between THI and TBKI activity classification. Source: THI OJK, 2022; TKBI 1 OJK, 2024; TKBI 2 OJK, 2025.

For instance, under the Green Taxonomy (THI) 1.0 2022, economic activities were categorized using a three-tier “traffic light” system. This consists of green (activities that cause no significant harm and improve environmental quality), yellow (activities with no significant harm but requiring further verification), and red (activities that are environmentally harmful). In contrast, the Indonesia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (TKBI) 1 and TKBI 2, released in 2024 and 2025 respectively, simplified the classification into only two categories, green (activities that align with Indonesia’s NDC commitments), and transition (those in the process of shifting toward greener operations). In turn, this reclassification has created inconsistencies, as some activities categorized under THI 1.0 are no longer included under TKBI 1 and 2, and vice versa. As a result, investors and institutions face confusion about which taxonomy to adopt, contributing to regulatory uncertainty and hesitancy in financing decisions.

Moreover, the Energy Shift Institute has criticized the taxonomy’s inclusion of mining activities within the “transition” category, arguing that such leniency contradicts Indonesia’s ambition to become a leader in green industrialization (Yudha, 2025). According to them, this “loose” categorization risks reinforcing Indonesia’s dependence on coal and other extractive industries, ultimately increasing carbon emissions rather than reducing them. As a result, there might be more greenwashing investments.

Furthermore, beyond the taxonomy itself, other regulatory challenges, such as overlapping land-use policies, complex permitting procedures, and inconsistent renewable energy incentives, further exacerbate risks and weaken investor confidence. Consequently, this could further impede the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) targets towards a green economy.

2. Weak Enforcement Efforts

Another critical challenge hampering the advancement of green financing in Indonesia lies in the weak enforcement mechanisms in verifying and monitoring green investments. A credible green financial system must be grounded in clear, verifiable, and transparent standards to ensure that financing genuinely supports environmentally sustainable projects. However, in practice, Indonesia’s green investment classification often depends on self-declaration by financial institutions and borrowers rather than independent verification.

For example, in the Palm Oil Plantation Green Taxonomy, several assessment criteria rely on self-reported compliance with Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and Good Handling Practices (GHP). In other sectors, green classification merely depends on certification ownership. This approach has also drawn criticism from TUK Indonesia’s Executive Director (TUK Indonesia, 2024), Linda Rosalina, who argues that green taxonomy should adopt clearer and more robust classification standards. This is because many companies holding sustainability certifications still contribute to environmental degradation, human rights violations, and even illegal operations. As a result, investors often struggle to distinguish between genuinely sustainable projects and those that merely claim to be green or widely known as greenwashing.

A prominent example of such greenwashing can be seen in Indonesia’s current nickel mining industry, which frequently portrays itself as part of the national green energy transition, even without clear quantitative and positive impact on the environment. The Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) and surrounding mining operations in the Halmahera Island, North Maluku, for instance, have been reported to violate the human rights of local communities, cause severe deforestation, pollute air and water sources, and emit significant greenhouse gases (Climate Rights International, 2025). Despite these extensive damages, the government has taken little to no action, seemingly viewing such projects as opportunities to advance its industrial downstreaming agenda. Moreover, Indonesia currently lacks a specific legal framework that criminalizes environmentally destructive or rights-violating practices under the guise of green investment. This regulatory gap has further blurred the boundaries of what constitutes a “green” activity within the green taxonomy, revealing the government’s weak enforcement capacity and its inability to ensure that sustainable finance principles are upheld in practice.

3. Lack of Incentives

In Indonesia, the government has already introduced several fiscal incentives to accelerate the growth of green investments, such as tax allowances, tax holidays, import tax exemptions (such as value-added tax (VAT) exemptions on imports or duty exemptions), and government-borne VAT (PPN DTP). These measures are important because, until now, investing in green projects, especially renewable energy, has been seen as not financially attractive. The government’s Basic Electricity Price (BPP) scheme does not offer electricity prices that match the high costs of building renewable energy plants (Pusat Studi Energi UGM, 2021). As a result, investors see renewable energy projects as unprofitable and choose not to invest.

This challenge is further confirmed by Nurul Ichwan, Deputy for Investment Promotion at BKPM. He stated that many investors remain hesitant, fearing that high electricity prices caused by high production costs could limit consumer demand and increase operational risks (Arief, 2025). This concern is particularly significant given that most investors in renewable energy projects are foreign private entities whose primary objective is profitability. Therefore, fiscal incentives such as tax reductions play a crucial role in lowering production costs, making electricity prices more competitive and, consequently, more attractive to consumers.

Furthermore, according to research conducted by Pusat Studi Energi UGM (2021), existing incentives can improve the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) on renewable energy projects. For instance, import tax exemptions can raise IRR to 14.36%, while a five-year tax holiday can increase it to 12.85%. These incentives enhance IRR by directly reducing upfront investment and operational costs, allowing investors to recover their capital faster and achieve higher profitability over the project’s lifetime. In essence, they address short-term liquidity and feasibility challenges, making projects bankable while the market, infrastructure, and technology continue to evolve.

However, these incentives alone remain insufficient. The same study projected that, with or without import incentives, the economically feasible selling price for solar power plants (PLTS) still exceeds the regulated BPP-based purchase price in most regions. This indicates that the government must develop more innovative and targeted fiscal mechanisms to attract investors and make green projects economically viable.

Moreover, in the long run, fiscal incentives could lead to dependency, especially if they are poorly targeted, indefinite, or not tied to measurable performance outcomes. Therefore, such incentives, like tax holidays or exemptions, should be applied selectively to projects that meet specific sustainability criteria or during the early investment phase to stimulate market entry. To ensure long-term sustainability, the government should also gradually shift its focus toward addressing the structural causes of high renewable energy costs. This includes the limited availability of reliable transmission grids and energy storage infrastructure, as well as Indonesia’s historical dependence on fossil fuels. Addressing these issues is critical because conventional power plants only face ongoing operational costs from continuous fuel consumption. In contrast, nearly all costs in renewable energy projects are incurred upfront during construction and technology deployment (Colyer & Cory, 2025).

Thus, instead of relying on continuous fiscal incentives, the government’s long-term priority should shift toward building a supportive ecosystem. This includes improving infrastructure, streamlining permitting processes, and clarifying market regulations to enable renewable energy to compete independently over time.

Case Study: How China Scaled Up Green Financing and Became a Global Leader in Renewable Energy

Reflecting on Indonesia’s case, it is clear that several structural and policy gaps must be addressed to accelerate the growth of green investment. These challenges, ranging from regulatory uncertainty to weak enforcement and limited incentives, have hindered the country’s ability to attract and sustain large-scale financing for green projects. To better understand how these barriers can be overcome, it is useful to examine how other countries have successfully navigated similar challenges. One prominent example is China, which has emerged as a current global leader in green economic transformation.

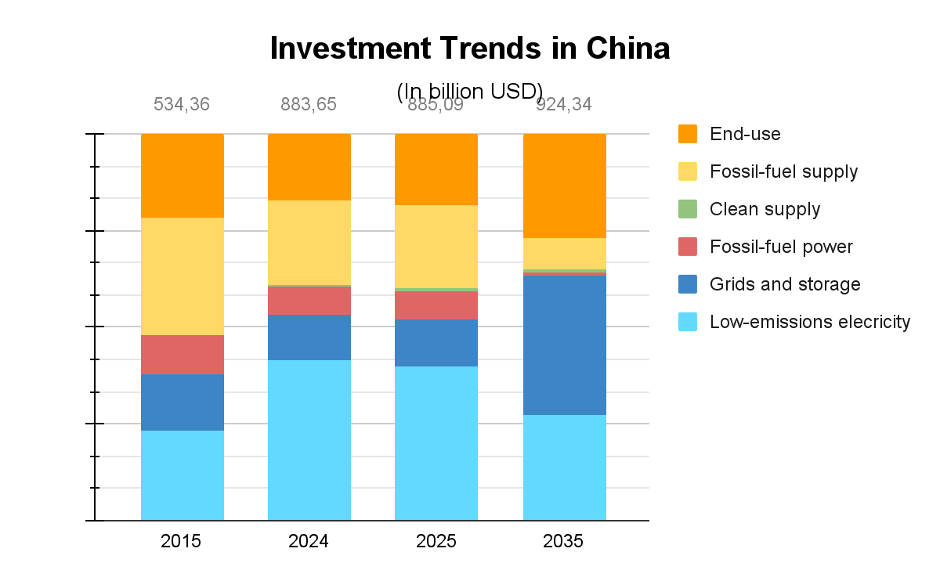

In 2023, China is the world’s largest generator of renewable energy, producing over 140,000 GWh of electricity (IRENA, 2023). This figure far exceeds that of Brazil (57,445.7 GWh) and the United States (52,346.4 GWh), reflecting China’s massive commitment to renewable development. However, this progress is impossible without substantial capital inflows into the clean energy sector. According to the International Energy Agency (2025), China’s total energy investment accounts for 4.4% of its GDP, with a growing focus on low-emission electricity, power grid upgrades, and energy storage development to enhance renewable integration and system reliability.

Figure 2. Energy Investment Trend in China 2015 - 2035 (STEP). Source: International Energy Agency, 2025.

From a regulatory perspective, China’s success in attracting green investment is underpinned by clear and comprehensive green finance frameworks. The People’s Bank of China introduced the Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System, aiming to mobilize and incentivize private capital participation while restricting financing for polluting projects. These guidelines promote public–private partnerships (PPP) and encourage market-based mechanisms to scale up green investments. Moreover, the Green Finance Endorsed Project Catalogue and the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT) with the EU provide clear classifications of economic activities eligible for green financing. These frameworks ensure that only projects contributing directly to sustainable development are recognized and supported, reducing the ambiguity for both domestic and foreign investors.

Although China currently lacks a specific law to criminalize greenwashing, existing regulations such as the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and Trademark Law serve as gatekeepers that prevent companies from falsely labeling or exaggerating their environmental performance to mislead consumers (Woo, 2025). Lastly, China’s success is also supported by strong fiscal incentives and policy intervention. The country has issued over 107 policies at national and provincial levels to accelerate green financing (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022). For instance, companies issuing green bonds are eligible for direct tax reductions and preferential access to financing. These comprehensive incentives and frameworks have significantly boosted China’s ability to channel capital into sustainable sectors, highlighting the importance of public intervention and private investments to enhance the net-zero emission goal by 2060.

Conclusion: What Indonesia Can Learn from China’s Green Energy Transformation

Drawing lessons from China’s success, Indonesia can adapt several strategies that align with its own economic and regulatory context. First, the government should strengthen public–private partnerships (PPP) to mobilize private capital, particularly in renewable energy and grid development. Those are the areas where Indonesia continues to rely heavily on state financing. Second, Indonesia needs a more robust and consistent green classification, especially for sectors currently labeled as “transition,” such as nickel mining and coal-based downstream industries. Clearer boundaries will prevent high-emission projects from receiving “green” financing and undermining decarbonization efforts.

Additionally, Indonesia already provides fiscal incentives such as tax exemptions for renewable energy components, but their implementation and targeting must be improved. The government could adopt sunset clauses, such as limiting tax holidays or import duty exemptions only until 2030 or until adequate grid and storage infrastructure are developed. This is done to avoid long-term dependency while still accelerating market growth in the short run.

Furthermore, unlike China, Indonesia still lacks legal consequences for greenwashing, which could weaken investor trust. Therefore, establishing a dedicated regulation that criminalizes misleading sustainability claims, while also providing strong monitoring and enforcement, would improve accountability and signal credibility to investors. In conclusion, by tightening existing policies and introducing targeted reforms, Indonesia can transform its current challenges into catalysts for progress. This approach would unlock the full potential of green finance to drive sustainable growth, restore investor confidence, and secure a resilient, yet low-carbon future for Indonesia.

References

Arief, A. M. (2025, August 13). Investor EBT Masih Ragu Investasi di Indonesia, Pemerintah Siapkan Insentif. Katadata. https://katadata.co.id/berita/energi/689c4481e3c62/investor-ebt-masih-ragu-investasi-di-indonesia-pemerintah-siapkan-insentif

Asian Development Bank. (2022). GREEN BOND MARKET SURVEY FOR INDONESIA. Metro Manila. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS220536-2

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2022, April). China Green Finance Policy Analysis Report 2021. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/policy_analysis_report_2021_en_final.pdf

Climate Rights International. (2025, July 23). Indonesia: Nickel industry harming human rights and the environment. https://cri.org/indonesia-nickel-industry-harming-human-rights-and-the-environment/

Colyer, T., & Cory, S. (2024). The future of renewable energy in Indonesia: 2025 and beyond. Oliver Wyman. https://www.oliverwyman.com/our-expertise/insights/2024/oct/investing-in-indonesia-energy-transition.html

Country rankings. (n.d.). https://www.irena.org/Data/View-data-by-topic/Capacity-and-Generation/Country-Rankings

Difa, I. S. Y. (2025, June 12). Indonesia attracts US$18.8 bln in investment via ESG scheme. Antara News. https://en.antaranews.com/news/359133/indonesia-attracts-us188-bln-in-investment-via-esg-scheme

Greenwash Index. (2025, May 8). Green Taxonomy Isn’t Green: TuK INDONESIA Calls for Genuine Change. https://greenwashindex.tuk.or.id/green-taxonomy-isnt-green-tuk-indonesia-calls-for-genuine-change/

Green Fiscal Policy Network. (2023, January 26). 5 Barriers that hinder green financing | Green Fiscal Policy Network. https://greenfiscalpolicy.org/blog/5-barriers-that-hinder-green-financing/

Green Taxonomy: A Guidance Note by UNESCAP. (n.d.). [Slide show]. UNESCAP. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/Session4_Green%20Taxonomy.pdf

Guidelines for establishing the green Financial System. (n.d.). http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4048320/3712404/index.html

INSENTIF FISKAL UNTUK MENDUKUNG INVESTASI PEMBANGKIT ENERGI BARU DAN TERBARUKAN PLTS DAN PLTMH. (2021). In Pusat Studi Energi UGM. Pusat Studi Energi UGM. https://pse.ugm.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/Insentif-Fiskal-untuk-Mendukung-Investasi-Pembangkit-EBT-Research-Brief-PSE-Mei-2021.pdf

Rahmah, N. N. (2025, August 21). Kemenkeu Gelontorkan Rp27,9 Triliun Insentif Pajak untuk Transisi Energi. Katadata. https://katadata.co.id/ekonomi-hijau/investasi-hijau/68a6f448ab9b9/kemenkeu-gelontorkan-rp27-9-triliun-insentif-pajak-untuk-transisi-energi\

TAKSONOMI HIJAU INDONESIA. (2022, February 20). Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. https://www.ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/info-terkini/Documents/Pages/Taksonomi-Hijau-Indonesia-Edisi-1---2022/Taksonomi%20Hijau%20Edisi%201.0%20-%202022.pdf

Taksonomi untuk Keuangan Berkelanjutan Indonesia 1. (2024, February 11). Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. https://ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/info-terkini/Documents/Pages/Taksonomi-untuk-Keuangan-Berkelanjutan-Indonesia/Buku%20Taksonomi%20untuk%20Keuangan%20Berkelanjutan%20Indonesia%20%28TKBI%29.pdf

Taksonomi untuk Keuangan Berkelanjutan Indonesia 2. (2025, February 11). Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. https://ojk.go.id/en/Publikasi/Roadmap-dan-Pedoman/Sektor-Jasa-Keuangan/Keuangan-Berkelanjutan/Documents/Indonesia%20Taxonomy%20for%20Sustainable%20Finance%20(TKBI)%202025%20v2.pdf

Woo, K. (2025, April 29). Green claims under scrutiny: Legal risks of greenwashing in China. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=a2feab81-d90c-4d1d-a089-04c61d4d2377

World Energy Investment 2025 - China. (2025). In International Energy Agency. International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2025/china

Yudha, S. K. (2025, July 29). Taksonomi Hijau Indonesia dinilai terlalu longgar, perlu direvisi. Republika Online. https://esgnow.republika.co.id/berita/t04x4n416/taksonomi-hijau-indonesia-dinilai-terlalu-longgar-perlu-direvisi

Yustika, M. (2024). Renewables Energy Investment Trends Decarbonization Indonesia Asia Unlocking Indonesia’s renewable energy investment potential. In Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/IEEFA%20Report%20-%20Unlocking%20Indonesia%27s%20renewable%20energy%20investment%20potential%20July2024.pdf

Comments

No comments for this post